Crossing points, contested spaces

A conversation between Joseph Harrington and H. L. Hix

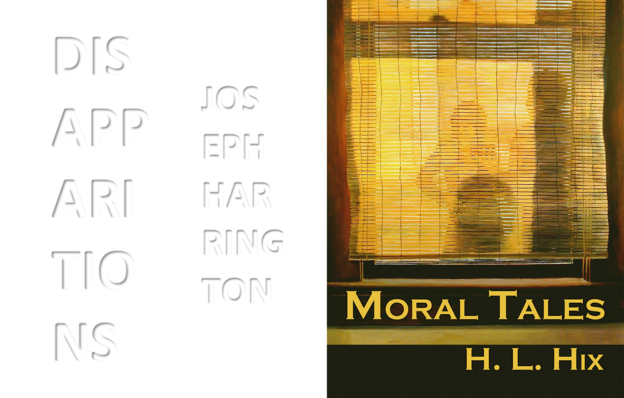

Joseph Harrington and H. L. Hix have perceived their work as being “in conversation” for quite some time, so the strength of their shared sense that Harrington’s recent Disapparitions and Hix’s Moral Tales were intent on listening in related ways led them to formalize their conversation. The result is the following inquiry into attention, attunement, genre, and other matters of writerly — and human — concern.

H. L. Hix: No doubt it makes more sense to open our conversation by asking about a very particular moment near the start of Disapparations, but one strong sense I have from the whole book is that it is a whole. Calling it a poetry “collection” wouldn’t do it justice: its continuity and structure are those of something designed as a whole, rather than of something gathered into a whole. Would you talk about how this happened? (Did you first have the vision of the whole and then compose toward it? Did one portion or element happen first and suggest the others? …) And about what significance this has for you?

Joseph Harrington: I’m delighted that it seemed like a whole! I guess I look back on it as an investigation that led from one point to the next. It started with a sense I had of present-day U.S. Americans’ being somehow spiritually insubstantial — like living ghosts. Phantoms, specters, apparitions — they’re gossamery. You can see right through them. They’re lightweights. They’re not good or evil enough for either heaven or hell. Anyway, I followed my first, rather quirky, association with ghostliness: sounds that I heard on shortwave radio as a kid. Some of them sounded like the muffled voices of spooks. Other voices recited random lists of numbers, as though they were enacting some punishment ladled out by Zeus. It turned out those disembodied voices had a lot to do with espionage. And I remembered that (at least during my childhood) spies were called “spooks.” So, I explored that specter-spy connection. But then I realized that I’d have to deal with a third meaning of “spook” in the mid-twentieth-century U.S., namely, as a racial slur directed at African-American people. Eventually, it became clear to me that these three meanings converged — and led back to that initial feeling about our national character (or national lack of character).

Speaking of spiritual (in)substantiality, I found Moral Tales fascinating — starting with the title, which, in the U.S., seems kind of like labelling a can of food “Stuff that Is Good for You!” To call someone “moralistic” is a put-down. You’ve thought a lot about the relation of poetry to philosophy and vice versa; for instance, your recent book Say It Into My Mouth makes ample use of quotations from Wittgenstein. But how do you see poetry connecting with moral philosophy? With virtue ethics?

HLH: For me, the strongest connection between poetry and moral philosophy is the intimate relationship both have to attention. Others have given elegant articulations of this connection recently. Warren Heiti, for example, in his book Attending, distinguishes “two genealogies in ethical psychology,” one that he calls Humean and one he calls Platonic. For Humean moral psychology, he says, “the ethical agent is an actor: his primary responsibility is to change the world.” For Platonic ethical psychology, by contrast, “the ethical agent is a witness: her primary responsibility is not to change the world but to understand it.” Her “proper work is attending.” Against the predominance of the Humean vision in contemporary moral philosophy, Heiti argues for the Platonic, and he finds predecessors in Simone Weil, Iris Murdoch, and others. I share Heiti’s inclination toward that moral vision, and his sense that it is allied with rather than opposed to poetry.

Lucy Alford takes a different approach in her Forms of Poetic Attention. If Heiti gives a genealogy of attention, Alford gives a taxonomy, distinguishing various modes of transitive and intransitive attention in poetry. She is careful not to leap to the conclusion “that cultivating attention leads necessarily to moral improvement,” but she does offer the “more modest proposal” that “poetic attention can cultivate the necessary but insufficient grounds for ethical response.” Practicing poetic attention, Alford contends, “might lead to a refinement of perception or a honing of our capacities for judgment, pattern recognition, and discernment, requisite preconditions for compassion and responsibility in relation.” There is still the task of applying those capacities to moral ends, but the honing of them prepares for such application. I find Alford’s case, like Heiti’s, persuasive and valuable.

That would be one way (not the only way, but one way) to talk about your Disapparitions: as a paying attention to things most often ignored or repressed or forgotten. There’s a felicitous figure for such attention-paying very early on. In the first paragraph of the first “Spook” section, talking about your dad’s shortwave radio, you say: “My dad taught me to tune with a fine touch: the slightest of movements could bring you out of the barking static and electronic glissandos, into the clearing where somebody spoke.” How important is that ideal of fine tuning, to this book and to you as a poet and person? (I’m identifying you with the first-person speaker in the book; correct me if I should loosen that association.)

JH: Well, on the most basic level, fine tuning the sounds of words is important to me, whether it’s the spoken cadences of the sentence or the musical rhythm of the line of verse (and the book contains both). You have to hit the right frequency in order to hear the transmission clearly.

But on a more thematic level, as metaphor, I think you’re right — I want a fine tuning of attention, of noticing, especially the things we are inclined to avert our eyes from. Alford’s “more modest proposal” seems like a good starting point for thinking about poetry and morality. I’m no utilitarian, but I think we in the Global North ask too much of poetry, sometimes. It is not a necessary and sufficient condition; writing or reading a poem certainly makes something happen, but not the same thing as delivering food to starving people in a war zone.

I guess learning to pick up the right frequencies means picking up on the right details — and on what is unsaid. When I do, I’m amazed at what I’m hearing. I hadn’t realized that people heard ghosts on the radio from its very inception. I honestly did not know that military intelligence used U2 spy planes to surveil protests during the Civil Rights Movement (they’re still doing that, by the way, only with more sophisticated technology). The more of those details you know, the higher-resolution your understanding. Disapparitions is certainly concerned with ignored, repressed, or forgotten (or just unfamiliar) histories, as well as what’s haunting them. When you look into such things, you have a better understanding of how power is based on deep-seated, unconscious images.

But by the same token, a more finely-tuned perception can also occasion a certain fear and trembling — you can’t unknow what you know, and what you witness or what you know can place an ethical demand upon you that you may or may not know how to respond to. I think of the end of the film version of Max Havelaar: confronted by the atrocities in the Dutch East Indies, he shouts at a portrait of William III, “In your name! In your name!”

But of course the portrait is “just” an image, not the flesh-and-blood person and certainly not an ideal form. In the first section of Moral Tales, you give Plato’s parables, metaphors, and hypotheticals a fresh, contemporary recasting in verse — as in this example, which will be familiar to many:

. . . Imagine humans underground,

in a cavernous haunt, its entrance wide and open to light,

but distant from the chamber itself. From childhood on,

they’re fixed in place, securely bound at neck and legs,

seeing only what’s in front of them, unable to turn

their heads. . . .

. . . and all they can see are the shadows of statues. Plato famously banished poets from the Republic and was suspicious of all artists, since they present mimetic images as though they were Truth. But your rendering of the parable of the cave shows that it is itself a kind of shadow of a statue: a fictional story inside a fictional dialogue. And you’ve (re)presented it in a poem!

How did you come up with this approach? Is this meant as a critique of Plato? Or a critique of poets? Or is it saying something about language or knowledge in general?

HLH: That first section is motivated by a couple of longstanding concerns, one particular to Plato, the other more general.

The concern specific to Plato is my sense that the perplexing anti-poetry passages aren’t hiccups, they’re hypocrisy. By that I mean they’re not hard to account for because they are disagreeable moments in what is otherwise agreeable, by analogy with the friend who seems in most matters very wise, but who voted for Trump. The issue is not that most of Plato’s views are compatible with mine, but his views on poetry aren’t, and this causes me problems because of my commitment to holding poetry in high regard. Instead, the problem is that those few moments of explicit dismissal contrast with the strong pattern, across all the dialogues, of Plato’s frequently “going poetic.”

The problem, in other words, is not that Plato’s explicitly-formulated position regarding poetry seems wrong (even stupid) to me, the way an anti-vaxxer’s position regarding vaccination seems to me wrong and stupid. The problem is that Plato says one thing and does another. When it comes to poetry, he doth protest too much, like the politician who publicly advocates making abortion illegal but who privately urged a sexual partner to have one.

The strong pattern in Plato, the one with which his dismissals of poetry are so dissonant, is that at the points of greatest pitch and moment the dialogues consistently turn to poetry. Logos always sets the stage in Plato, but mythos always steals the show. So I’m interested in those passages, the ones in which someone, often but not always Socrates, “waxes poetic,” and the first section of Moral Tales is a selection of such passages.

The more general concern is how we treat “great books” and other sacralized texts. Plato is in the category: we’ve all heard Whitehead’s pronouncement that the history of philosophy is “a series of footnotes to Plato” and Emerson’s that “Plato is philosophy, and philosophy, Plato.” This treatment shows up as literalism in relation to religious scriptures such as the Christian gospels, and as originalism in relation to political founding documents such as the U.S. Constitution. The mistake in this treatment is its attempt to derive the flexible applicability and authority of the text from the text’s own fixity, to find, in other words, its dynamic significance in its static character. That treatment results in such flagrant and consequential error as interpreting “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms” as if the referent of the word “arms” were static, repressing the fact that in 1791, when the Bill of Rights was ratified, arms granted a bearer the capacity to kill one person at a time, with a long pause necessary to reload after each shot, but a contemporary M-16 can fire at a rate of over 700 rounds per minute, and the attendant fact that in 1791 bearing arms did not enable an individual to commit mass murder, but today it does.

This treatment also shows up as a “forest for the trees” approach to translation that hews closely to what a text said at any cost to what the text does, an analogue of (here a nod to Ciardi) insisting on what the poem means, to the neglect of how the poem means. So the Plato and Marie sections both participate in the project of Moral Tales but also in my broader project of hitting “refresh” on various ancient sources of wisdom. In other books, I’ve done more than one translation (or, to use the term I appeal to in Moral Tales, more than one treatment) of the gospel, and more than one of the complete Herakleitos. The hegemonic approach to translating influential texts secures the institutions that have calcified around them (the Church around the gospel, academic philosophy around Plato), but it travesties the works themselves and their authors. I’m trying to take a different approach.

Is it fair to see something similar in Disapparitions, a working out in practice of an oppositional principle? I’m thinking of your observation in Poetry and the Public that “‘Poetry,’ before the culture wars of the 1930s, the subsequent Cold War, and high modernist/New Critical hegemony, described not a genre with a consensus definition, but a crossing point, an indeterminate and contested space in which new ways of writing emerged.” Am I out of line to read Disapparitions as an example of the kind of crossing point / contested space you identify there?

JH: Not at all. I think in the decades (!) since Poetry and the Public came out, mixed-genre, genre-queer or “trans-genre” writing (as David Lazar calls it) has become mainstream, a development I welcome. And “poetry” has become, among other things, the space where publishers and booksellers place any text that doesn’t fit clearly into any other category, which is OK by me. “Poetry is a verdict,” as Leonard Cohen wrote.

So, I guess that makes me closer to Benedetto Croce than to Plato — or Aristotle — when it comes to questions of genre; I read inductively, rather than deductively. I really do think you have to take each work of art on its own terms; I have a rather naïve belief that a text will teach you how to read it, if you read enough of it. And Disapparitions is really about reading — or rather, about how we perceive, encode, and construct meaning in the “texts” around us. And the effects our readings can have in the physical world.

The through-line in Disapparitions is a serial essay in prose, “Spook” / “Sp**k.” I didn’t want to try to condense its twists, turns, and complications into verse. However, at several points, it ramifies into verse experiments/excurses, most of which are responses (procedural, interpretive, documentary) to other texts.

One can write an essay in verse or a poem in prose, but I do think the prose/verse distinction is a valid (empirical, physical) one. It has to do with the rhythm of the spoken sentences vs. that of a musical phrase. It also has to do with pacing — how quickly the eye is forced or cajoled to move down the page, or how move across it. That’s a pretty broad distinction, but I find it helpful.

Nonetheless, there’s a wealth of resources historically associated with the categories “poem,” “essay,” “drama,” etc., and I encourage writers to make use of them, to mix and match them, based on what sounds and seems right for the particular piece they’re working on. No one creates ex nihilo. And those categories change over time; for instance, most of what are called “essays” nowadays I’d be more inclined to call short memoirs.

But there’s an institutional wall that is crumbling but has yet to be breached decisively: namely, that between “creative writing” and “scholarship,” in the academy. The sub-discipline of poetry is perhaps further along in this regard: the poet-critic is an increasingly common role, and it’s become uncommon for a book of poetry to come without endnotes or a Works Cited page. Obviously, Moral Tales straddles that divide. The “Myths” and “Fables” sections are creative translations/ interpretations of primary sources. Then there’s the “Glosses” section at the end, which is divided into two subsections, each corresponding to the first two sections of the book. The glosses “gloss” in a rather asymptotic or oblique manner. It seemed to me that there were about twice as many glosses as Myths for the first section, so I stopped trying to match them up and just read the former as a continuous poem or collection of aphorisms. There’s a more direct connection between the Fables and their glosses; the latter follow a more regular form, and there are patterns even though they are paratactic.

We usually think of “glosses” as a kind of scholarly term: for example, an explanation, translator’s note, paraphrase, or trot. Yours seem different here. Could you say something about the relation between the Myths and Fables on the one hand and the Glosses on the other?

HLH: It’s another way in which our books are “tuned to the same frequency.” You speak of points at which Disapparitions “ramifies into verse experiments/excurses, most of which are responses (procedural, interpretive, documentary) to other texts,” and that would work as a description of the Glosses’ relationship to the Plato and Marie de France sections.

Each section of each of the Glosses derives from or responds to one of the Plato or Marie de France poems. It’s easier to track in “Way Far Out Over Your Guys’s Yard,” where the eighth line of each stanza is a riff on one of the Marie fables, in the order in which the fables appear. (So “Because people love to hear bullshit, that’s why” in the first stanza of “Way Far Out…” responds to “That rooster was deliberate, / as humans are who choose bullshit,” the moral of the first Marie fable after the prologue. And so on.)

My hope for the Glosses, though, is that their history (that the process of their composition included conversation with the Plato and Marie de France poems) does not exhaust their destiny. I hope that both Glosses stand, and that either can be read, as a “freestanding” work with its own integrity. So “Way Far Out Over Your Guys’s Yard” does include fifty “samples” from Marie, but they’re among hundreds of samples from other sources. I hope it would offer its reader interest and pleasure and value even if it were encountered, or published, completely apart from the Marie de France fables that are “behind” it.

But surely every “trans-genre” text is working out its part/whole and origin/destination relationships in fear and trembling, just as Moral Tales is. Take one part of Disapparitions, say these two lines: “Do not give in / in big things only.” I would receive those words in one way, had they been issued me by a parent or teacher as part of a scolding for being stubborn when I was ten. But I receive them differently as part of the poem on p. 26, itself part of the section “Spies in the Living House,” itself part of the book Disapparitions. How would you speak to (speak about) the part/whole and origin/destination relationships at play in Disapparitions?

JH: There are some lines in your “Glosses” that answer that question better than I could:

While the teacher told the others about their world,

I was working to decode the radiator’s knocking.

Even then I knew the Secret spoke its secrets in secret,

that news about my world wasn’t being offered me

from the front of the room but from off to one side.

I’ve done my fair share of offering news from the front of the room, and certainly, some of Disapparitions does that. But as a poet, I’m more interested in what we make of the world around us. We (mis)hear things. We decode things we think are messages or discern hidden meanings. And sometimes the de-crypted messages end up reflecting the news as in a funhouse mirror. Sure, you can hear the announcer on TV, but can you hear the screaming from the basement?

As I say, the prose work “Spook” / “Sp**k” runs through most of the book. It’s an essay in the Montaignesque sense, weaving and bobbing from one topic to a related one, quoting this and quoting that, moving from one register to another, without an overarching argument or narrative. But then there are these serial verse poems that are like side-trails that break off from and then rejoin the main path. I think any of them stand on their own. I’ve published excerpts from “Spies” in journals, and apart from the context of Disapparitions, they read differently — even more otherworldly, perhaps. But a reader wouldn’t necessarily see the relation between them without the prose connective tissue.

Jack Spicer wanted to hear “Martians” or “spooks” emanating from “The Outside” and record the result as poems. “Spies in the Living House” is like a Spicer-esque readymade. The polymath Konstantin Raudive transcribed the voices of the dead he heard over the radio; he calls them “Electronic Voice Phenomena” (EVP). In Breakthrough: An Amazing Experiment in Electronic Communication with the Dead (1971), he lists these short utterances by category, which seemed to me a rather dry way to connect with the great beyond. I wanted to hear the voices. So, I wrote as I read through the messages, sometimes transcribing, sometimes combining, sometimes mishearing or deliberately misreading. And it ended up sounding like a dialogue — or multi-logue — between spirits (including my own).

For the next serial poem, “Lincolnshire Poacher Variations,” I started out with an actual encoded message from British military intelligence from the 1990s. I developed my own method for de-crypting it, which resulted in a grid of seemingly random words. So, I looked at it from first one angle, then another, trying to squeeze meaning out of it. In some sections of the poem, I excerpted words vertically or horizontally; in others, I read through the words as I turned the whole 90˚, 180˚, and so on; I did erasures, which is also a form of decoding. What I discovered is that (ironically) I heard in them sub-genres of poetry (pastoral, elegy, song, etc.). In other words, genre became both heuristic device and compositional prompt, which are what genre is. It is one way of decoding or shaping texts.

The poem “Dear Future,” started as 60ish pages of handwriting I’d produced over the course of one winter. I boiled it down to about 3 pages that seemed interesting or significant. I didn’t write it with the book in mind; but then I realized that the investigation I had undertaken had everything to do with the future. The final poem, “The Eyes,” attempts to bring together the historical threads that “Spook” / “Sp**k” identifies. It was a more deliberate documentary poem, a collage of snippets of primary sources connected by minimal narration/narrative. I selected the snippets based on how central they were to the story and on how hard they hit me in the gut or made my eyes bug out. It has its ghostlier demarcations, but it’s also the most directly connected to the prose.

The thing is, when I went back and re-read “Spies” and “Lincolnshire,” having written the rest of the manuscript, they read differently. They went from being procedural experiments to sounding more like oblique commentaries on what comes after them, in the book. I hadn’t intended that. It was kind of spooky. And honestly, I didn’t realize it until the book was in production. Hopefully the reader remembers some of the moments from those early poems as they read the rest; or maybe even re-reads them.

Likewise, if your playful translations/interpretations of Marie de France’ fables were presented by themselves, I would read them very differently than I do with the bookends of the Plato excerpts and the Glosses. My Norman French is a bit rusty (ahem), but from what I can tell, they read like very contemporary but faithful translations of the fables, even down to the iambic tetrameter couplets. Marianne Moore had La Fontaine, you have Marie de France. What attracted you to her fables, in particular? And why pair them with Plato?

HLH: I arrived at the fables “backwards.” Several years ago, I was introduced to Marie through being assigned a section of my university’s first-year Honors survey, taught at the time with a common reading list and a “great books” orientation. The Lais were in the curriculum, and teaching them interested me in Marie. Seeking out more of her work, I learned that only one complete translation of the fables into English is available, and one small selection (23 of the 102 fables).

I learned, in other words, that my prior ignorance of Marie’s work participated in our longstanding neglect of it. The reasons for that neglect are plain, and also bad. For one thing, the fable is a low-status genre commonly pigeonholed as children’s literature. This is a bad reason in itself, made worse by being applied to Marie’s fables in bad faith: no one applies it to Animal Farm, and as Harriet Spiegel rightly notes, Marie’s fables “are not fables for children.” That these fables were written by a woman is an even worse reason for their neglect. The fables have been neglected, too, because Marie’s own Lais have overshadowed them, never mind that this is as canon-crimped as neglecting Bartleby or Billy Budd because Moby-Dick is so swell.

So one reason for my interest in the fables is recuperative: they’ve never had the readership they deserve. The pairing with Plato, though, has more to do with my critique, the one we touched on earlier, of the standard approach to translation. What I’ve elsewhere called “example blindness” has worked to narrow existing translations. By example blindness, I mean consent to the (usually unstated) premise that a translation is acceptable if it produces a correlative to the original writer’s results, but not if it replicates the original writer’s process. My Plato and Marie both try to resist this.

Marie spoke of her fables as translations, but she didn’t construe translation in the terms most prevalent today. As Sharon Kinoshita and Peggy McCracken point out, Marie’s fables “are identified as translations,” but they’re really “rewritings.” Marie “changes her narratives, emphasizing different elements of the story, omitting or adding to the plot,” and so on. R. Howard Bloch makes the same point. Marie is “obsessed by the transmission of sources, by the process of translation, and by the cultural transformation that translation implies,” he says, but the word she applies to her process doesn’t square with the contemporary English word “translate.” Marie uses “the same polyvalent expression for translation that … serves to define poetry itself — that is, the little word traire, meaning ‘to draw,’ ‘to treat,’ ‘to translate,’ ‘to betray.’” Marie’s fables are themselves translations; I’m trying to heed the principles she herself used in translating them.

So I am aiming for a “faithfulness” to the original, but not faithfulness to the word-by-word reference of the original so much as faithfulness to the tone of the original. Marie’s fables are funny. They’re smackdowns. That’s what I hope my versions in Moral Tales capture.

Yet again, I’m thinking of our projects as tonics to one another. One moment that lets me get at the connection I’m perceiving (or making up!) is in the third “Spook” section, part of the prose “connective tissue” you mentioned earlier, that listens to the “spooky signals” that “still populate the spaces in between the stops” on the radio. There are short-wave enthusiasts, who “use empirical methods to solve mysteries,” and EVP researchers who “use empirical methods to prove there is a mystery in the first place,” and “Targeted Individuals,” who already “have all the proof they need that spooks are real.” But I’m not reading Disapparitions as an attempt to arbitrate between differing views and steer me the reader to a correct understanding of the phenomenon; I read it as a way of registering the mystery, “tuning in” to people’s strong and varied responses, and so on. In my head I assign descriptors such as “recuperative” and “inquisitive” and “exploratory” to Disapparitions, rather than “didactic” or “declarative” or “propositional.” Is this at all consonant with how you think of your book?

JH: Well, as I say, I think of it as “investigative,” because I genuinely followed a trail of clues. That’s probably why there are a lot of question marks in the book (after questions that may or may not have answers). There are some declarative utterances, but I offer them provisionally. Your book is called Moral Tales and not “Morality Tales”; likewise, I’m trying to observe and record my responses to that which is, rather than trying to be hortatory. The “morals” of Marie’s (and Aesop’s) fables are not aiming to make you a better person, but to make you more aware and, perhaps, shrewder. I’m not so much interested in the question of whether ghosts exist: they clearly exist, insofar as the discourse around ghosts exists. But I’m interested in how we talk about ghosts — and each other.

There are references to and quotations of other writers throughout Disapparitions (Avery Gordon, Jacques Derrida, Terrance Hayes, Sam Greenlee, et al.), so there’s also a strong intertextual and interdisciplinary sense — I’m not making this stuff up by myself, but I am trying to piece it together for myself. Perhaps that makes it an example of “speculative ethnography,” which the anthropologist Yamuna Sangarasivam describes as “an experimental methodology that bends time and space in order to view a subject through many genres, discursive forms, human stories, and complex theories simultaneously.” Perhaps.