Violent holidays in Russia

An interview with Kirill Medvedev

Note: Kirill Medvedev’s brief, shocking “On the Day of My Thirty-Seventh Birthday” details what happens to a revolutionary who has just been involved in killing the president. After acting as a lookout and messenger during the assassination, he mistakenly shoots and kills a fan, whom he mistakes for the secret services but who simply wanted an autograph. Facing this revelation, the poet thinks to himself, “Shit … what a missfire. / A tragic missfire, a mistake, / which means the good-for-nothing president / is still alive.”[1]

This poem, like much of Medvedev’s work, is simultaneously ferocious and subtly introspective. The radical multihyphenate — Medvedev is just as well known for his essays, music, and activism — does not only condemn state violence but also examines our own complicity in supporting oppressive structures, either through deed or thought. The coldness in tone with which he does so makes the effect of his poetry all that much more striking. It is not that he doesn’t understand the consequences of revolution, but rather that he recognizes the necessity of being ready to face the aftermath as the first step to changing the world. Consider, for example, this clip in which he sings his Russian-language translation of Catalan singer-songwriter Lluís Llach’s protest song “L’Estaca” from the back of a police van with calm self-assurance. In fall 2021, he was detained for ten days after participating in a protest against the construction of an elite apartment building in a historic section of Moscow, where current residents fear that the work will damage their own homes.

Such provocations and direct engagement go part and parcel with Medvedev’s poetics as well. As critic Marijeta Bozovic puts it, “Medvedev’s fundamentally avant-garde gesture of institutional critique rests on a new sincerity; and on a belief that poems, poets, and poetry must retain an active responsibility and a role to play in transforming the surrounding socio-ethical world.”[2] In 2003 for instance, on his personal website, he declared that he was done with the literary field as such, opting to publish only what he could by his own labor and money. Then, perhaps most notably, in 2004 Medvedev gave up copyright to his works, declaring that he could not possess such rights and requesting that all future editions be “pirate” editions identified as having been produced without contracts or permissions, and soon after announced a five-year minimum ban on publishing poetry altogether. Despite, or in fact because of, these self-imposed bans and challenges, Medvedev’s poems have picked up a sizeable audience in the last two decades for their straightforwardness and his willingness to break with convention both in and outside of the texts themselves, particularly in a tradition where free verse is, relatively speaking, a recent development.

For all these reasons, his poetry was a perfect fit for my course devoted to Russian prison literature, which I offered in spring 2021. Eager to make the best of teaching on Zoom, I invited Medvedev to speak with my students. The poems that we read don’t take place in prisons, and yet they speak to themes we had been discussing all semester: justice, violence, crime, and punishment. In this sense, they allowed us to widen the scope of the course in exciting and productive ways. The questions my students generated collectively, it seems to me now, spoke to a desire to understand better a poet who likely doesn’t fit the usual bill for them — a poet whose politics bleed into his writing and whose political actions are imbued with a performative streak. In particular, after a semester focused primarily on state repression, they were intrigued by poems that seemed to flip the script and call for violent political protest, or that at least engage with these ideas in such a candid manner.

This conversation, which occurred on the last day of classes that semester (in fact, my last day of teaching at Swarthmore College), followed our reading of Medvedev’s “Victory Day,” “On the Day of My Thirty-Seventh Birthday,” and “The wife of an activist who died under mysterious circumstances.” It was transcribed and edited by Grace Sewell. Student participants include Malhar Acharya, Faith Becker, Dylan Clairmont, Michael Eddy, Elizabeth Hohn, Lucas Katz, Carissa Kilbury, Jonathan Lehr, Jesse Li, Ava Posner, Grace Sewell, Bing Xin Tu, Nicolas Urick, Robert Wickstrom, Max Winig, and others. — José Vergara

Lucas Katz: Thank you for coming to our class. To start, why did you become a poet?

Kirill Medvedev: In elementary school, you recite some poems as part of the school program. At first, it was my fascination with the sounds of poetry. I didn’t know why — sounds were very mystical and surprising to me. Second, there is the cultural legend, universal but pronounced in Russia, about the Poet as a figure who lives in a special way and feels more than other people. Finally, I think that poetry is a political narrative. Poetry helps people find a common language when there is no other way to do so. These three stages led me to become a poet.

Michael Eddy: I’m curious about how you feel about critics who dismiss your work and say that it is not a form of poetry. Both “Victory Day” and “On the Day of My Thirty-Seventh Birthday” break away from traditional poetic forms.

Medvedev: When I wrote “Victory Day” about seventeen years ago, I felt that a new establishment was forming and that it was important for me not to become part of it. I felt an illusion of normalization. Putin’s regime was based on unsolved ethical, social, and political problems. For example, a huge part of the wealth created through collective labor ended up in private hands in the ’90s, and the new elite appointed a leader to defend this property. I wasn’t a political person in the ’90s. I was only interested in art — sex, drugs, rock and roll. It seemed to me that the normalization of this approach to power was formed out of the chaos of the ’90s, and I didn’t want to be a part of it. I had to look for new ways to exist as a poet without becoming complacent in this new reality. I was influenced by ideas about globalism, which is popular even now in Russia. There was something challenging about it, so I tried to personally adopt the ideas associated with great political and social movements around the world. Also, I think I wanted to construct conceptual “barriers” around myself so that I would have to figure out how to get around them. Of course, this challenge was rather individualistic, I think.

When I began writing poetry in free verse about twenty years ago, I was worried about a negative critical response. I viewed such a reaction as a confrontation between conservatism and progressive innovation. Now, I don’t see this opposition, perhaps because my free verse is no longer read as radical. I’ve also cast aside a linear idea of progress, which has led me to experiment with different poetic forms. Some elements of “archaic” forms can communicate a progressive and even revolutionary message. In general, the question of form is not as much of a problem for me personally or in Russian poetry in general as it was twenty years ago.

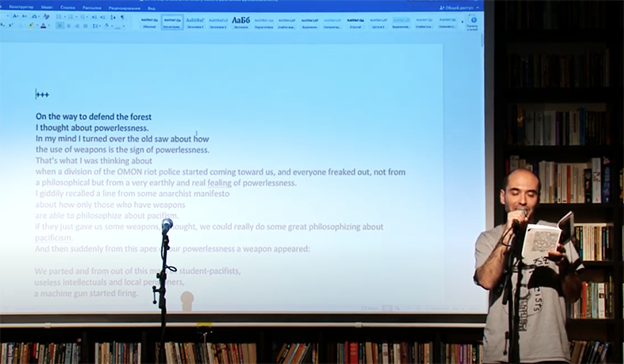

A recording of a poetry reading featuring work from Medvedev’s collection It’s No Good.

A recording of a poetry reading featuring work from Medvedev’s collection It’s No Good.

José Vergara: Who do you see as your literary predecessors?

Medvedev: There are so many. I like poets who are distant from me in terms of ideology. I like [Rudyard] Kipling who was a sexist imperialist. I like the poet Nikolai Gumilev, a Russian imperialist and Orthodox Christian killed by the Bolsheviks. I don’t know why, but their poems offer a kind of challenge. I don’t agree with their ideas, but their writing is very impressive and strong. These poets build a hierarchy that I don’t like, but they do so in a convincing way, because they are very good poets. My dream is to make an anthology of reactionary poetry, in which I would gather powerful poems from different authors — poems that I might hate politically and ideologically. Of course, I also like left-wing authors such as Vladimir Mayakovsky, Victor Serge, Bertolt Brecht, and Nazim Hikmet.

Jonathan Lehr: Your poems that we read for class involve a violent rejection of authoritarianism. In light of the pro-Navalny protests happening in Russia right now, do you think that there is a path forward for Russia that is nonviolent? Is peaceful protest enough?

Medvedev: It’s not the violence that is really important, but the readiness for violence. Even if you don’t want to act violently, if the authorities see that you are ready for violence, they are left with only two choices: respond more aggressively or retreat. This readiness for violence is the willingness to risk your own life. You might not like the radicalism itself — it is hard to love revolution as it is usually associated with violence — but you have to convince your enemy that you are ready to put your own life on the line. To convince them, you have to be ready to take violent action.

The situation with Navalny today is such that doctors were finally allowed to see him, and he has stopped his hunger strike. As I understand it, he more or less recovered. At the same time, his organization was marked as an extremist group and his headquarters in various cities were destroyed. This is how the authorities are preparing for the elections, because they are afraid of the so-called “smart voting tactics” that Navalny is calling for. Most of all, the regime is afraid of the unification of different ideological wings of the opposition — liberals, socialists, communists, civil activists. My comrades and I believe that the worst thing that can happen to the regime is precisely this unification. On the one hand, Navalny fueled hatred of the elites and the rich. On the other, there is the pro-Soviet part of the opposition. If we don’t want this process to be a total failure and don’t want a bloody revolution incited by a minority, then we have to do our best to become a majority. I think that the political key is the unification of the opposition.

In response to the latest wave of protests, Medvedev recorded this statement on the topic of “how to make our voices louder.”

In response to the latest wave of protests, Medvedev recorded this statement on the topic of “how to make our voices louder.”

Robert Wickstrom: In “The Wife of the Activist,” you turn to activists in the labor movement. What would solidarity among different social movements actually look like? How could such movements inform issues like prison abolition and reform?

Medvedev: Politically, I think that we need a broad democratic movement. In order to solve problems concerning prison and repression, we need a new and inclusive platform. At the same time, we don’t have to abandon our ideological and political divisions. My friends and I used to speak often about how to build a broad coalition without forgetting our ideals as socialists. I think that this process is difficult and urgent. Of course, we support the movements against police violence and prison reform initiatives.

Elizabeth Hohn: Both “Victory Day” and “On the Day of My Thirty-Seventh Birthday” are named after holidays, when one would expect there to be celebration instead of violence. What were you trying to communicate with these ironic titles?

Medvedev: Thank you for this observation. I honestly didn’t think about how holidays are mentioned in both poems when I was writing. I don’t think it’s a coincidence. As for my birthday, there is a reference to the age of thirty-seven. This number has a special meaning in the narrative, as many poets died at this age. Some of them, such as Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov, died violently. The fact that I really had this dream on my birthday is something that I had to include in this poem. Perhaps it is psychoanalytic: the time comes when you kill or you will be killed. In Russia, at least, holidays like Victory Day are very dangerous because people want to have a good time and drink a lot. The police think that it is necessary to keep order on such occasions. This increased security leads to various excesses and incidents.

On the other hand, people interested in politics participate in political actions on Victory Day, including those prohibited by the authorities. Often, this leads to police brutality. In some sense, this is the thing that keeps these holidays alive. For example, last year on Victory Day, police in Moscow dispersed the leftist march, which centered around the slogan “This is not your victory.” This slogan is addressed to the regime, which instrumentalizes the holiday for its own interests. This is an example of how brutality manifests on Victory Day. When I wrote the poem, I didn’t mean any irony concerning the date, but now I see it.

Ava Posner: In both “Victory Day” and “On the Day of My Thirty-Seventh Birthday,” people in power and those in subordinate positions are capable of the same acts of brutality and murder. Was this a purposeful choice meant to communicate that everyone has the capacity to commit these acts regardless of how they are justified?

Medvedev: Violence is the principal word here. If you look at violence from the point of view of ethics, of course, any struggle for justice should take place without violence. Historically, we know that any struggle for justice — especially revolutionary struggle — includes radical violence and the murder of opponents. I don’t like terror as an element of the struggle for justice. I also don’t like the use of state terror in Russia today or the methods used before the revolution when revolutionaries were brutally killed by various government officials. At the same time, I understand the emotional appeal of violence and terror to people who might have no other way out. Of course, seeing how the police and government officials behave in Russia now, I understand people who chose to commit violent acts in the past.

Nicolas Urick: Should we, or do you, view the police as solely components subject to the state/“system,” or as self-determining individuals? In other words, how far out does this circle of culpability extend?

Medvedev: My poem “Victory Day” suggests that if the police cannot be brought to justice through the courts, they should bear responsibility, but their relatives and people who happen to be associated with them should not be held responsible, too. It is an attempt to make a political position out of your emotion. This ethical reflection is not just an abstract thought. After the recent revolutionary events in Ukraine and the failed protests in Belarus and Russia, there are websites where you can find the addresses of the policemen who behaved the most brutally. This is a call for revenge, not only revenge against the authorities, but also on their children, fathers, mothers, and so on. It’s a terrible thing, but at the same time, I know that the question of how to respond to the police officers who tortured your friends and loved ones is difficult. The only thing I can say definitively is that people who just happen to be close to those who commit violence shouldn’t suffer at all.

I don’t know whether it’s more of an ethical or political position, but it’s something I thought about when writing these poems included in my book, Attack on City Hall. The whole book is dedicated to violence. When writing it, I thought about how the politicization of a person happens. How does a person become a political subject? I think that this happens through one’s own relationship to legacies of violence inflicted in order to advance a particular creed. It is not just a question of justifying violence; it’s a question of responsibility. No matter how you identify in political terms — Communist, socialist, liberal, nationalist — you are responsible for the violence committed in the name of your idea. To accept this responsibility is to become a truly political subject. The whole book is a reflection on this idea.

Jesse Li: How has your approach to activism and political organizing and their relationship to your poetry changed? In the future, what will be the greatest challenges to achieving the coalition you’ve spoken about?

Medvedev: In my long career as an activist, I was shocked to discover that you can write some texts and sing some songs, and there are people who are convinced by your ideas. It’s not enough to hope that others will transform these ideas into political action, however. You have to take action yourself alongside others. Regarding the Russian left and the international left, I think that the most difficult task is how to combine nostalgia for what we’ve lost with the need to move forward and renew society. For example, the structures of the welfare state are being destroyed by the neoliberal order. We have to protect such systems by appealing to the state, because these systems provide a basic level of protection for everyone.

Looking into the future, we don’t want to think much about the state because we want more horizontal power structures that are less alienated from the people. How to resolve these two problems is a major task facing not only Russia but also the world. For the Russian left, this problem is even more serious because of the collapse of the Soviet Union, which convinced people that it’s better not to hope for change because change may lead to something worse than the status quo. I don’t share this view, but I understand where it comes from. Radical changes often lead to more chaos and insecurity for vulnerable groups. The recent events in Egypt, Libya, Syria, and Ukraine are evidence of this phenomenon. As a result, leftists are often reluctant to participate in politics because they fear change. Everyone will say that although they don’t like their lives and that the authorities don’t care about them but they fear that it could be worse. It is a challenge for the Russian left to reclaim the idea of progress.

Malhar Acharya: How was your experience of running for municipal office in Russia as a leftist? What did you learn from this experience?

Medvedev: Thank you for this question. I have very positive memories of this election campaign, and I hope to run again. For me, it was a new way to communicate with people. When you come to them as a neighbor and candidate instead of as an activist from a particular organization, you come to them with promises to help them in concrete ways rather than abstract ideas about socialism and anti-Putinism. You try to solve the concrete problems of everyday life. It seems obvious, but then again, most of the people involved in liberal activism in Russia are trained in theory rather than practice.

I campaigned to reconstruct an old cinema in our neighborhood that was burned down in the ’90s. The majority of people living in the area have a very personal connection to the cinema, which housed a school and an institute. The fact that the cinema has been in ruins for twenty years is traumatic for the people personally, socially, and politically. However, this trauma is repressed because there are other issues in everyday life that take precedent. When I came to collect signatures for the reconstruction of the cinema, this trauma resurfaced. It led to two different types of reactions. On the one hand, people shared fond memories of the cinema. On the other hand, people expressed anger towards the people who were responsible for destroying the cinema. While they were angry with politicians and oligarchs, I was the target of their anger because I reminded them of this tragedy. I had to transform people’s memories of the cinema into political discourse. In general, local politics interests me very much because it combines the tangible, materialistic concerns of everyday life with cultural, ideological, and political experiences of the people. Local politics gave me the opportunity to see how these two realms define “politics” in the genuine sense of the word.

1. Translation by Joan Brooks.

2. Marijeta Bozovic, “Poetry on the Front Line: Kirill Medvedev and a New Russian Poetic Avant-garde,” Arcade, August 11, 2015.