Drenched

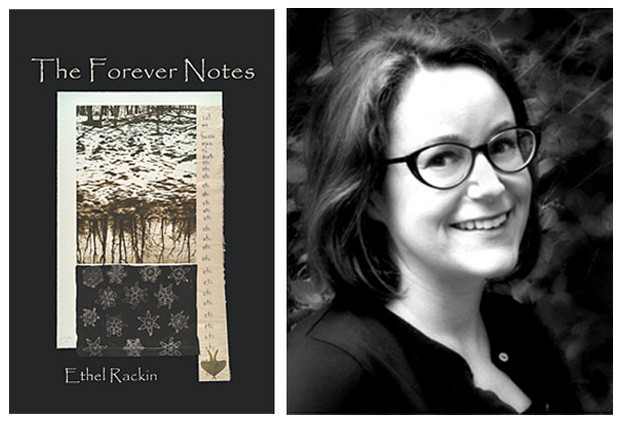

A review of Ethel Rackin's 'The Forever Notes'

The Forever Notes

The Forever Notes

“My Sister’s Drawings of Trees,” from the third and final section of Ethel Rackin’s The Forever Notes, concludes in lines that could serve as a primer to the book’s development of the lyric, especially Rackin’s amendments to its use as an instrument of discovery and dissent. This poem begins singling out for consideration one of many drawings made by a sister with the precise deictic “This,” but ends in three lines hinged by a simile (“like ghosts”) that turns the poem back on itself in a “generative act” like the one described at its center:

This red-lined tree with leaves —

where does it come from

where does it go?

Time we play

queen & servant

for a day —

how I wish

it could be different.

A generative act

splits the street

with no trees at all,

still becomes greener.

Flowers that wilt and bloom.

We learn to grow things

like ghosts

we put things away. (46)

In an act of mental sounding, the poem touches off the final line, moving back up into its one stanza to review the ways we might “learn to grow things / like ghosts” and also “put things away” like ghosts, as well as the ways growing things and putting things away relate to each other. The doubled simile and the repetition of “things” pressurizes the placeholder generalization so that the word that comes closest to meaning merely “nouns” (both concrete and abstract) ripples with curious, competing possibilities: in the context of these multiplying lines, “things” might be living, literal, and sustaining (like flowers and food) or conceptual (like ideas and poems) or alive but lethal and informative (like diseases).

These multitudes draw the eye up through the poem’s expertly broken and syntactically fragmented lines, returning to the surface of the opening question to circle it, as is often done in “red-lined” editorial ink for emphasis, expansion, or deletion. Within the poem’s compressed consideration of sibling play and children’s attractions (their “drawings”) to natural objects, however, Rackin’s lyric also recalls and recasts Emerson’s meditations on the relationships among human sight, imagination, and moral pursuits in “Circles,” an essay that begins, “THE EYE is the first circle; the horizon which it forms is the second; and throughout nature this primary picture is repeated without end … and under every deep a lower deep opens.”[1] The ungraspable expanses of the natural world may thwart answering “where does it come from / where does it go?” but in Rackin’s poetics the infinitude of experience leads to deeper concentration and more intimate contact with the words and symbols through which the world is known.

In the ambitious re-creation of Emerson’s dual figures of concentricity and depth supporting his contention that the “universe is fluid and volatile,” Rackin’s “My Sister’s Drawings of Trees,” like most of the poems of The Forever Notes, exhibits characteristic properties of what Elizabeth Willis has termed the “late lyric,” a descriptor Willis uses to clear up persistent misunderstandings of the lyric as a kind of confessional verse resulting in epiphany and transcendence of personal and historical specifics. Contemporary instances of the late lyric don’t evade their histories, but instead “exis[t] in a present that contains the past” — a past that stirs and is stirred by the present.[2] In the context of Willis’s theory, one that recognizes the universe Emerson sees, the things “we learn to grow” and “we put … away” in Rackin’s poem about sibling role-playing and creative freedom include drawings of trees and youthful wishes for a different world. But among the things cultivated and the things stored out of sight are traces of the dolls, childhood, spool necklace, and Christian name put away in Dickinson’s famous poem of maturity, “I’m ceded — I’ve stopped being Theirs —.” “My Sister’s Drawings” encourages this association with the famous Dickinson poem of self-confirmation through its trademark em dashes and the syntactic doubling[3] of the lines “with no trees at all” and “like ghosts,” and in the earlier lines’ allusion to the poem’s central trope of a queen who replaces the infant servant to actual and religious fathers. Dickinson’s gestures of dissent against man-made rituals of salvation gather far more quietly in Rackin’s poem about play, representation, and the power of creativity.

In containing the past that holds Dickinson’s lyric, Rackin’s poetics reroutes the expected circuits of intertextuality. The particles and particulars of Dickinson’s poem circulating in “My Sister’s Drawings” don’t so much direct reading to Dickinson as through its shorthand history of American selfhood envisioned as isolate, regal, and aristocratic, in which individuality is always a matter of ascension and separation, from servant “we” to royal “I.” The presence of other mediums in Rackin’s poem — performance (playing queen and servant) and drawing — complicates the poem’s ekphrastic movement to open a horizon of a remediative consideration. Here, Dickinson’s poem that ends in self-coronation and declarations of self-sovereignty (“With Will to choose, or to reject, / And I choose, just a Crown —”) opens into “a lower deep” through Rackin’s reopening of its terms for power, oppression, and childish imitation.

This opening and circling are generative acts of the intellectual imagination animating The Forever Notes, not only redrawing poetic relationships but also reviving the lyric’s most basic elements. Repetition of words and phrases within poems and from poem to poem demonstrates the late lyric’s capacity to “evoke alternate experiences” and to “provoke an excess of meaning.”[4] In poems “You lie in a tree told sure,” “Story where I kept you,” and “You and the laborious night of trees,” Rackin avoids enjambment in favor of lines beginning traditionally with capitalized words but ending openly, unpunctuated, as in “You and the laborious night of trees”:

Trees and the night around you

You and the laborious night of trees

Trees and the night around you

Laborious night

You and the trees (19)

Emerson’s cosmic horizons seem to intersect at several points with Stein’s insistence, her method of rolling words over and over a line to fill various syntactical positions, gaining and halting momentum in ways that shake habits of consciousness to expose the luxuriance of the everyday. Rackin’s lyric pressurizes this play of reference, shifting “you,” “trees,” “laborious,” and “night” to provoke many simultaneous identities for speaker and addressee. In other poems, like “Leaflets,” repetition operates in ways similar to patterns established in HD’s early poems in which desire fuels vision in violent bursts:

There are those whom I need

to be singing

there are those who are singing

so I tear myself — (48)

The rending of self and song and of self by song illustrates the late lyric’s tendency to push and rupture the boundaries of identity rather than to repair or preserve them. Rackin’s work scatters the speaking self sometimes violently, sometimes playfully, often joyfully. These are volatile poems, but their explosiveness often drives toward hope and receptivity. “A generative act / splits the street” and in splitting the street, traffic moves more freely, more dangerously and unpredictably, in two or more directions, like infinite lines radiating from the vanishing point of a sister’s drawing.

In these poems, the foundational materials of the lyric seem in a continual state of regeneration. Even the most poetically handled words, like “tree,” “flowers,” “dreams,” “leaves,” or “sea,” become not just revived but disturbing and uncontainable, detonated within the ample margins. The vocabulary of the idyll so frequently occupies Rackin’s poetry that, when terms from the modern world of consumerism and entertainment appear (as they occasionally and discreetly do), a vibrant recirculation of temporal and perceptual modes takes place, as in “How wonderful to go riding”:

And to feel the sadness

That loneliness leaves

When it leaves

How wonderful to go riding

To fall into that sadness and know it

The breath of fall and the buds that spring

To experience sales also

In the adrift of language’s departments

How wonderful to feel sadness

That springs from summer monuments (10)

The setting is almost entirely impressionistic, although the sense of lushness and intensity of understanding is certain. Images of the Romantic natural world press into the poem’s emotional alertness, although there’s little that explicitly ties the poem to a remote countryside where riding is an experience of being carried along for the ride rather than driving or pedaling to a destination. Pleasure seems central to this poem, especially the pleasure in opportunities to move at a speed that allows one to notice subtle shifts in season and to recognize layers of emotion, “to feel the sadness / That loneliness leaves / When it leaves,” layers condensed by contemporary (and literary) inclinations towards closure and the contentedness emotional clarity is supposed to bring. Wonder, the roots of which mean either “a sight” or “a panic,” is clearly separate from private happiness or a release from the modern world of consumerism and bureaucracy. There is wonder in “sales” and in the lingo of contemporary popular discourse, too — “the adrift of language’s departments” is an ingenious clause, letting “adrift” drift out of modifying departments and into double occupation as subject of the prepositional phrase and newly minted noun, conspicuously awkward in its unfamiliar pose.

Rackin’s orientation in widely recognizable poetic materials accomplishes The Forever Notes’ greatest renovations of the lyric, its ability to gesture toward and even coax into view the untapped, untraveled expanses of perception. This embrace of old, even clichéd matters defies the new and improved, “fresh” and “emergent” criteria dominating contemporary poetry, but in Rackin’s poetics, that defiance is far from reactionary. Instead, The Forever Notes argues, implicitly and persuasively, that the lyric, even stripped down, remains a potent resource for imagination, beauty, and explorations of consciousness. Rather than find new subjects and forms for poetry, this stance implies, we must look harder at the ones we think we already know. “Meet me in the cabin,” the book’s first poem, presents a tiny, puzzling accumulation of repetition and metaphor (that also demonstrates Rackin’s archaic but multifunctional presentation of titles) that directs attention to some of the lyric’s most primitive matters — desire, love, and the struggle for immersion in the present:

Meet me in the sea

Meet me where our love’s a shirt

Drenched, dried out, and drenched once more (5)

Structuring this love lyric urging an erotic reunion, the miniature anaphora of “Meet me” turns the public emphasis of repetition marking the epic into the lyric’s intimate voice. Familiarity itself is the poem’s focus; familiarity comes from repetition and wear, like the homely (and metaphorically compounded) love shirt drenched and dried, over and over again. The poem’s delight comes from its speaker’s expectation of the cycles of meeting, love, drenching, and drying — of what’s known, but not completely, ever. Rackin sets aside the epiphany’s shock of recognition to wring from the lyric the slow, fluid volatility of knowing — our widest, most complex and elusive horizon of recognizing — what we see and feel, for days and for centuries, again and again, once more.

1. Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Circles,” in Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Richard Poirier (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 166.

2. Elizabeth Willis, “The Arena in the Garden: Some Thoughts on the Late Lyric,” Telling It Slant, Avant-Garde Poetics of the 1990s, eds. J. Mark Wallace and Steven Marks (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002), 225.

3. In her Emily Dickinson: A Poet’s Grammar (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987), Cristanne Miller identifies Dickinson’s use of “a single phrase to cover two nonparallel syntactic contexts or to describe two different subjects” (37) and names this technique “syntactic doubling.”