A detour from more traditional paths of composition

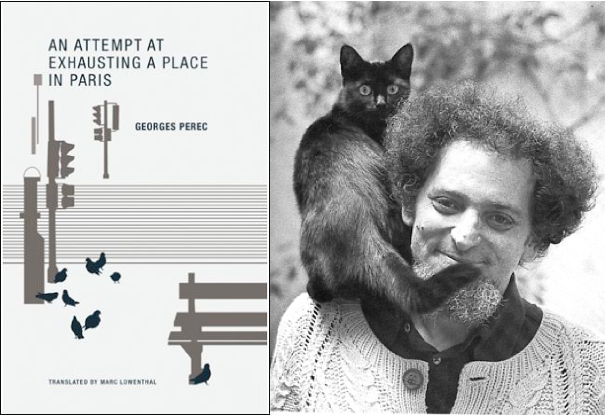

A review of 'An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris'

An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris

An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris

The objective of a Baudelairian flâneur or Situationist psychogeographer might be described as the revelation of what’s hidden in plain sight. With their modern walkabouts, these conceptual strollers break free of the direct lines of commuter travel and instead happily wallow in an inefficient dawdle. A close cousin, the aspirations of constraint-based writing can be said to be the exploration of the “potential” literature created via similarly artificial detours from more traditional paths of composition.

An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris was written by Georges Perec during a gray Parisian weekend in October 1974. The stated intention was to “describe … that which is generally not taken note of, that which is not noticed, that which has no importance: what happens when nothing happens other than the weather, people, cars, and clouds.” A nonambulatory flâneur, Perec sets himself up at a cafe in Place Saint-Sulpice to do as his directive epigraph of Life: A User’s Manual orders us to do also: “Look with all your eyes, look.”

Of course the underlying joke of An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris is the absolute impossibility of exhaustively documenting any environment, however quotidian, or any instant of time, however short, especially with the beautifully linear and limited tool of language. While pretending a goal and attitude of rigor, Perec’s simultaneous assumption of futility colors the work with a shade of melancholic comedy — a cosmic joke with failure and constant loss as the punchline.

Take for instance his quickly (and quietly) abandoned categories from the morning of the first day: “Outline of an inventory of some strictly visible things,” (which includes letters and numbers) “Trajectories,” (which includes the direction of the buses, and “Colors” (which are reductively plain, e.g. a “blue bag” and a “green raincoat”). These arbitrary categories slyly underscore their own arbitrariness (you could even say their own silliness). By beginning his project immediately with a feint at cataloging the infinite (e.g. trajectories) Perec initiates a one-person epistemological Laurel and Hardy routine.

Part of the comedy too is the Sisyphean cycle of trying, giving up, and then starting all over again. A poignant example of this occurs with Perec’s observation of buses through the city square. He’s constantly noting them:

The 96 goes to Montparnasse station (6).

A 63 passes by. A 96 passes by (11).

A 70 goes by, full (22).

In the middle of the work he interrupts to comment parenthetically:

(why count the buses? Probably because they’re recognizable and regular: they

cut up time, they punctuate the background noise; ultimately, they’re

foreseeable

The rest seems random, improbable, anarchic; the buses pass by because they

have to pass by, but nothing requires a car to back up, or a man to have a bag

marked with a big “M” of Monoprix, or a customer to order a coffee instead

of a beer…) (22–3).

But then the following morning:

Buses pass by. I’ve lost all interest in them (29).

Yet soon enough he’s back to noting them:

A bus: “Percival Tours” (31).

A 96 goes by (42).

The 63 (45).

The 96 (47).

Constraint-based writing might also be described as the poetic residue of someone else’s thought experiment. So in addition to the re-realization of his chosen task’s impossibility, in Perec’s shifting categories and evolving real-time commentary, we’re also privy to other discoveries. For instance, due to Perec’s time-stamped headers, we get a sense of the speed of thought, at least of Perec’s, which feels both leisurely and focused. The reader gets, in other words, a very real sense of how long it takes Perec to write an entry so that, despite the noted impossibility, a rather vicarious understanding of Perec’s weekend is achieved.

Ultimately then the inherently doomed objective goal of exhausting a place in Paris leads us surprisingly to the successful portrait of a particular subjectivity. It’s a stunning and bittersweet act of intimacy and remembrance. For example in the following passage: the startling moment of Perec’s inclusion of the word “splendid.” Interrupting the stream of so-called facts, this simple adjective for a moment sights Paris pigeons uniquely through Perec’s eyes:

An 87. A 70. A 63.

Rue Bonaparte, a cement mixer, orange.

A basset hound. A man with a bow tie. An 86.

The wind is making the leaves on the trees move.

A 70.

It is one fifty.

SNCF parcels service.

The people from the funeral procession have entered the church

Passage of a driving-school car, a 96, a 63, a florist’s van, blue, which parks next

to the undertaker’s van and from which a funeral wreath is taken.

In splendid unity, the pigeons go round the square and return to settle on the

district council building’s gutter.

There are five taxis at the taxi stand.

An 87 goes by, a 63 goes by. (13–14)

This handsomely designed book from Wakefield Press also includes a moving translator’s afterword, which argues (thought provokingly if not entirely convincingly) that An Attempt can be seen as an “inverted version” of Perec’s masterwork Life: A User’s Manual. Certainly larger than its slim dimensions indicate, An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris is, in the end, less a strategically flawed urban snapshot than a mysterious and craftily unauthorized autobiography.

A series of reviews of walking projects

Edited byLouis Bury Corey Frost